Off-the-back of COP26, the UN climate conference held in Glasgow in November, the spotlight is on the transportation sector to lead by example when it comes to reducing emissions. Aviation is often seen as the sector’s dirtiest culprit, despite only contributing to only 2.5 percent of all carbon emissions (1). Automotive on the other hand makes up 15 percent of all emissions. The aviation industry also has a history of leading the way i technological development .

Governments are moving to regulate the industry to meet climate targets. In the summer, the European Union introduced its ambitious ‘Fit for 55’ programme. Which aims to cut 2030 emissions by 55 percent to help it on its mission. For aviation, it includes a tax on kerosene in the EU, a requirement for carriers to blend it. To power flights, and the phasing out of free airline carbon market allowances. Additionally, all airlines departing from EU airports will need to uplift the jet fuel necessary to operate the flight before departure, to avoid fuel tinkering, which increases emissions.

In 2020 France implemented an ecotax of up to EUR18 on all tickets, while Germany announced similar measures, depending on which part of the world the flight was going to.

If a passenger is flying to a top bracket, category 3 country, beyond Europe, Central Asia and the Sahel in Africa, they will have to pay a tax of EUR58.73. Germany has added smaller taxes for countries that are closer by, and no commercial flights.

The pressure from politicians on the aviation industry to respond to climate change is only going to increase. Global carbon emissions must be cut by half by 2030 to stay below 1.5 degrees of heating, according to The International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC). But since 2009, IATA has only advocated halving aviation’s net carbon emissions by 2050 and only comparative to 2005 levels, far short of the IPCC target. The UN’s International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) predicts the industry’s emissions will not half but triple by 2050. Much progress needs to be made by all industry stakeholders to ensure this does not happen.

The preparations will impact the industry in multiple ways. For example, the residual values of older, high maintenance and fuel-hungry aircraft are likely to end up decreasing. The industry has a lot of work to do to meet the Glasgow Climate Agreement, and on the financing side.

What is ESG?

ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance, and it serves as a set of standards for a company’s operations or transactions that allow socially-conscious investors to review potential investments.

Environmental criteria could include the company’s energy use, carbon emissions, deforestation, or treatment of animals. It could also be the amount of exposure it has to environmentally dangerous commodities or fuels, as well as the ways it handles environmental risks. A company’s environmental practice could pose a greater financial risk, and that would also be taken into consideration.

Social criteria look at the company’s business relationships. Does the company work with suppliers that match its social policies, donate and fund local communities keep its employees satisfied? How well are customer relationships managed?

“ESG issues cover Environmental, Social and Governance Issues. There is more of a focus on environmental challenges. But it is important that the industry and governments don’t ignore the S and G issues.”

Sustainably-linked aircraft finance transactions

New technology aircraft have reduced the amount of CO2 emitted by aviation. The A320neo family, 737 Max, 787 and A350 are about 20 percent more efficient than their predecessors. Although that is to be welcomed, we all need to recognise that the combustion engine powered by fossil fuels is going to become a thing of the past and aviation needs to find a way of eliminating the use of that type of engine moving forward.

There have been a few aircraft transactions that are ESG-compliant or have used green financing.

In February 2020, French-Italian manufacturer ATR became the first commercial aircraft OEM to deliver an aircraft funded by a green loan. The five ATR72-600s, delivered to lessor Avation and on lease to Swedish carrier Baathens Regional Airlines (BRA), were financed by Deutsche Bank loan compliant with the Loan Market Association’s Green Loan Principles (GLP) (3).

In June, Korean Air announced that it would issue green bonds as part of a KRW200 billion (USD176 million) corporate debt issue to become the first carrier in South Korea to float ESG bonds (4). The carrier said it planned to use the proceeds to purchase newer technology aircraft that are better for the environment, such as Boeing 787-9s, and possibly Boeing 787- 10s.

A month later, British Airways closed a sustainably-linked EETC, which contained a sustainability-linked coupon step-up of 25bps which will be triggered by the airline achieving its sustainability performance target by 2025. The target is an improvement of CO2 per passenger per kilometre of flights flown in 2025 to 88.3g of CO2. Against a 2019 baseline of 96.1g of CO2, according to Ishka (5).

In mid-November, Banco Santander and Crianza Aviation structured the first sustainably- linked operating leases for certain Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 aircraft (6). Banco Santander acted as the ESG structurer of the deal. The transactions are linked to an MSCI ESG rating, which involves allocating percentages over the different criteria before they are combined and normalised relative to industry peers. The leases include a pricing mechanism to incentivise improvements in ESG performance.

At ISTAT Americas in Austin, Texas, in November, lessor chiefs spoke out about the increasing desire from airlines for ESG- compliant transactions when it came to sourcing new aircraft (7). Air Lease Corporation’s CEO, John Plueger, noted on a panel that “the environmental sustainability aspect cannot be overemphasised.”

That same month, ALC and Airbus announced a new ESG fund to contribute towards investments in sustainable aviation development projects, which will be open to other lessors. The deal includes the newest technology aircraft across Airbus’ product line, including the A220 – which according to the manufacturer, has 25 percent better fuel efficiency than previous-generation competitors.

More ESG transactions are in the pipeline, but a lack of an applicable set of ESG standards for aviation is holding back the development of green financing for the sector. There are more questions for investors than answers due to different ideas of what constitutes a “green” deal, and that needs to be rectified with an industry benchmark. Leading financiers in the

industry will need to work to develop such standards.

E-fuels and Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), which is made from non-fossil fuel feedstocks, is one of the most effective ways at reducing the carbon footprint of the industry in the short to medium term, but it is not looked at as a sole solution to helping the aviation industry reduce its carbon footprint. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) says SAF can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 80 percent (8).

Michael Weiss, ABL Aviation’s Chief Commercial Officer says: “All those in aviation need to recognise that aviation is a contributor to CO2 emissions, and we need to take responsibility to do our part in reducing the impact of aviation on the environment. It is recognised that aviation contributes approximately 2.5 percent of CO2 emissions globally, with that set to increase with more and more people travelling over the longer term, and in the absence of new technologies and efficiencies. We shouldn’t be defensive about it, because if we are, others will dominate the discussion and we won’t be masters of our destiny.”

“Sustainable Aviation Fuels are being developed, and several airlines have invested in providers of this type of fuel. Recently, United airlines used 100 percent SAF on a flight from Chicago to Washington DC, which is the first time that 100 percent SAF has been used on a commercial flight. By all accounts, this flight was a success. The issue with this form of fuel is the price and availability of SAF. There simply isn’t enough being produced and it will take time to ramp up the supply”, Weiss adds.

The state of the art of SAF market in 2021

On December 1, U.S.-based United Airlines became the first airline to fly a commercial flight with SAF with more than 100 passengers on board, including CEO Scott Kirby (9). It flew on a 737 Max 8 from Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport to Washington’s Reagan National Airport, using 500 gallons of SAF in one engine and the same amount on conventional jet fuel in another. Currently, airlines are only permitted to use a maximum of 50 percent SAF on flights. The plane flew 612 miles and used 75 percent less carbon dioxide than a flight with all traditional jet fuel, United said.

Virent – a subsidiary of Marathon Petroluem – and World Energy made the fuel, which is made from sugar from corn, beetroots, and sugar cane. Around 275 million gallons of SAF will be produced in 2022. Last year only 35 million gallons were made.

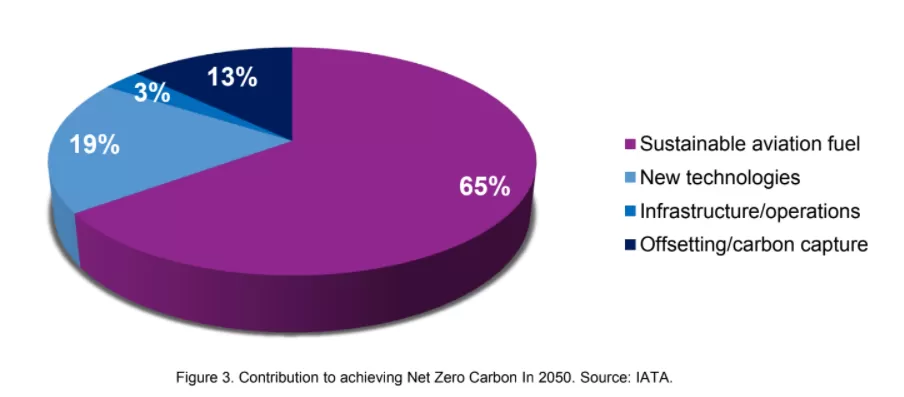

IATA has forecasted SAF to contribute around 65 percent of the reduction in emissions needed by aviation to reach net-zero in 2050, compared with 13 percent reduction from new, fuel-efficient aircraft.

The industry body believes infrastructure and operational changes will contribute to 3 percent of the reduction, while carbon offsetting/carbon

capture will contribute 19 percent (8).

However, some European LCCs are sceptical of this target (10). Ryanair, Wizz Air and EasyJet have said fleet renewal rather than large-scale investment in SAF will be the primary driver of sustainability for the airline industry in the short term. For example, Ryanair’s CEO Michael O’Leary has long touted the new LEAP engines on the Max Gamechanger aircraft as a way to significantly reduce fuel consumption. Having fuel-efficient aircraft only makes the industry greener if the airline is flying the same distance, it would have been before – therefore using less fuel.

One challenge is that, unlike United, many airlines do not have permission to use SAF yet. Many carriers need the supply chain and OEMs to develop the fuel, infrastructure, and aircraft to fly using alternative fuels.

Contribution to achieving Net Zero Carbon in 2050

Speaking at a Eurocontrol sustainability conference in November. O’Leary said Ryanair is also committed to 12.5 percent SAF target by 2030 but admitted that it would be a challenge to meet this target. Due to there being a question mark over its availability. For example, Neste, the world’s largest SAF producer, is promising to have an annual 1.5 million tonnes SAF production capacity. A drop in the water compared to the 52 billion gallons the aviation fuel consumed in 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (where flights were drastically reduced) (11).

There are also concerns that there should not just be too much focus on SAF.

Biofuels are not a long-term solution, as they are based on land-based feedstock and are often limited in quantity.

The implementation and cost of SAF for airlines still raise key questions. There needs to be more scrutiny on sustainability across the whole aviation supply chain. Regulators and fuel suppliers are among the other industry players that need to be held accountable. An airline cannot transition to green fuel unless regulation allows it, and the alternative fuel is available.

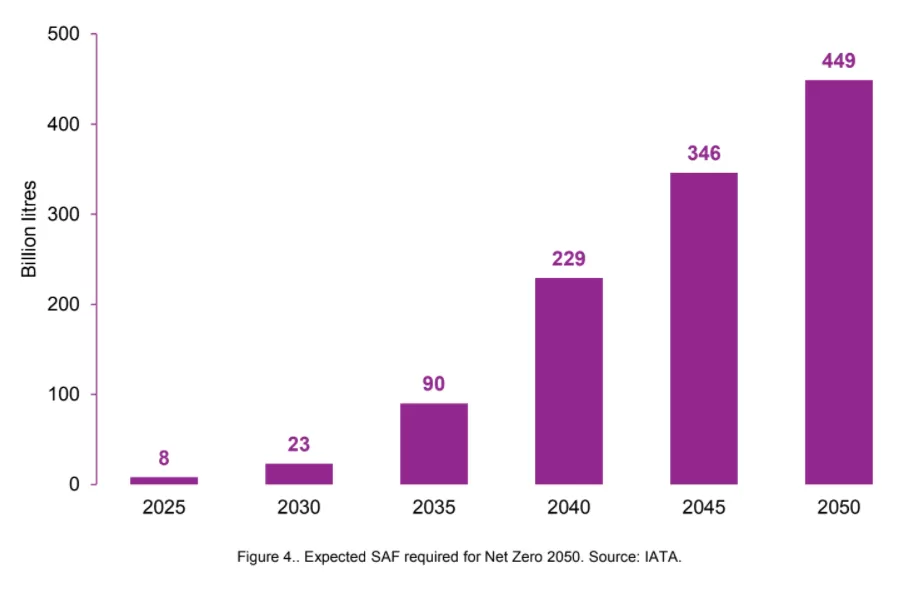

It will also require a massive increase in production (see chart below) in order to meet demand. The largest acceleration is expected in the 2030s as policy support becomes global, SAF becomes competitive with fossil kerosene, and credible offsets become scarcer (10).

Expected SAF required for Net Zero Carbon in 2050

Hydrogen and e-fuels

Robert Howarth, the David R. Atkinson Professor of Ecology and Environmental Biology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, together with Mark Z. Jacobson, Stanford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, authored the 2021 research paper “How Green is Blue Hydrogen?” (12). “Most of the hydrogen in the U.S. and Europe comes from natural gas. Using steam and pressure to convert the methane from natural gas into a so- called ‘grey’ hydrogen and carbon dioxide,” said Howarth said in the paper.

Blue hydrogen starts with converting methane to hydrogen and carbon dioxide by using heat, steam and pressure, or grey hydrogen, but goes further to capture some of the carbon dioxide. Once the by-product carbon dioxide and the other impurities are sequestered, it becomes blue hydrogen, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

The process to make blue hydrogen takes a large amount of energy, according to the researchers, which is generally provided by burning more natural gas.

“In the past, no effort was made to capture the carbon dioxide by-product of grey hydrogen, and the greenhouse gas emissions have been huge,” Howarth said. “Now the industry promotes blue hydrogen as a solution, an approach that still uses the methane from natural gas while attempting to capture the by- product carbon dioxide. Unfortunately, emissions remain very large.”

For aviation to achieve net-zero emissions, e-fuels must be a vital part of the equation. They are produced from a mixture of carbon dioxide and hydrogen, meaning that they can be produced at scale with no limitations, making them a more long-term solution than biofuels.

One of the main challenges with e-fuels is the high cost of production and that much of the infrastructure to use them has not been developed yet, meaning that they cannot currently compete with biofuels. There needs to be the fast introduction of policies that specifically support the development of these alternative fuels. The technology transition needs to take place now if enough e-fuels will be produced to power the whole aviation industry. As e-fuels require renewable electricity, investment in the transformation of the electricity grid infrastructure is imperative, though it will likely take several years.

However, there have been some encouraging noises from the OEMs regarding hydrogen- powered aircraft. At ISTAT EMEA in Edinburgh, Airbus and Embraer spoke about the potential of hydrogen propulsion to help power their future aircraft (13). On two separate panels, Airbus said it planned to develop hydrogen- powered aircraft by 2035. While Michal Nowak, Marketing Director at Embraer said the Brazilian OEM would be prepared to make “an aircraft of reasonable size powered by hydrogen” within that timeframe. But he warned that hydrogen infrastructure that would power such aircraft may need a further 10 years to be ready.

Michael Weiss says: “Hydrogen is promoted by many as a new panacea for aviation. Yes, the combustion of hydrogen should only produce water, thus virtually eliminating carbon dioxide emissions. However, the problems with hydrogen can be classified into two major problems: production, and technology. The production of hydrogen itself may cause a lot of pollution – research by Cornell University (14) and other institutions has shown that the production of hydrogen may be more polluting than fossil fuels” (15).

“Green hydrogen is a good clean fuel, but there is still a long way to go to produce enough of this form of hydrogen. In a recent interview, Emirates President Sir Tim Clark summarized the practical problems of using hydrogen in aviation. For example, liquid hydrogen needs to be cooled to minus 273°C, which poses a challenge for distribution-underground storage tanks and hoses that will freeze at this temperature. The volume of hydrogen is three times that of fossil fuels. Which poses a major challenge for storing hydrogen in sufficient volumes.

It is not just a question of putting liquid hydrogen into the space that is currently reserved for fuel in current technology aircraft, and it would be interesting to analyse which will be the impact on the economics of the asset”. “We need to be honest and not suggest hydrogen as a practical solution in the short term. Hydrogen will help, but it’s a way off”, Weiss adds.

Electric

Electric planes have been around since the 1970s, but air travel uses a lot of energy. Batteries are too heavy to support commercial jet aircraft sizes or long-distance flights. In June 2020, the largest electric plane ever to fly took off. The Cessna Caravan 208B took off from Grant County International Airport in Washington State, able to carry a maximum of nine passengers.

Due to these design challenges around the batteries. The large commercial OEMs believe it could take decades before a fully electricity-run commercial aircraft is built, which has the potential to carry hundreds of passengers for

long distances. Hybrid aircraft may be the answer in the shorter term.

“Electric propulsion has also been suggested as the way forward. But battery technology will need to be improved significantly for a suitable narrowbody aircraft replacement to be produced. The batteries are heavy and are, at this stage, not able to store enough energy to make a narrowbody replacement viable in the short term”, Weiss adds.

Source : ABL aviation.

Be the first to comment on "Aviation addressing the climate crisis"